Modern Paganism & The Problem of Necromancy

Commentary on the revival of old ways in a new world

The problem with our modern, Western pagans is that they do not genuinely believe in their gods, they merely believe in believing in them. My ancestors believed, but I do not know how they believed. I confess that I do not know what it is like to live in a world in which there are gods.

Collin Cleary, Summoning the Gods

Deep in rural Arcadia, a fierce cultural battle is taking place regarding the place of a new minority of Greek religious apostates, seeking to change the dominant status quo towards its values. You’d be excused for thinking this is a headline from 450AD, but it’s in fact from 2025.

This time around, it is a pagan minority seeking to establish itself in a staunchly Christian land. For the first time in 1700 years, the worship of Pan has returned to his native Arcadia, with the construction and official opening of a temple dedicated to Pan, Zeus, and Dionysus in the small village of Kalliani. Of course, this was not done without protest from their hyper-Orthodox countrymen:

This specific action, which attempts to restore practices and perceptions of a religiosity of bygone eras, causes us sadness and concern. It is not a return to a bright and glorious past, as its followers claim, but a regression to a dark world, dominated by human passions and demonic works.

Church Metropolitan Nikiforos of Gortynos

Days later, the archeologist and designer of the temple was arrested. In an interestingly modern fashion, not for heresy, but the violation of local building codes. And despite threats from executives for more arrests if the temple opens due to these abhorrent and illegal construction violations, the temple was opened with great ceremony on March 8th, as planned.

As small as this event was, taking place in a village of just 200 people, it serves as a compelling microcosm of larger religious trends in the West. There are several components here: the deterioration of Christianity and its loss of the ability to enforce itself as a hegemonic institution, a resurgence of expressly ethnic interests and worldviews, and a romanticism for the pre-Christian past—all resulting in a new competing culture and the establishment of official sites for its practice.

But there is something else about this opening ceremony to serve as a representative of larger themes. Did your eye catch it in the photo? Towering above this beautifully quaint temple, built by the calloused hands of this tiny village, stands a monstrous power line.

A temple built in mimicry of those built 2500 years ago, attended by practitioners adorning themselves in the style of Achaeans, reciting the hymns and rituals of Delphic processions… and behind it is looming this giant metallic spire, no doubt powering the night clubs, airports, and gas stations of distant Athens. One photograph, two worlds. It could just be me, but it feels just a little kitsch of an arrangement, doesn’t it? A question keeps ringing in my ear, what exactly are we doing here? It feels reminiscent of Byzantophile Orthodox Christians who proudly beat the pulpit with icons from the Hagia Sophia, seemingly forgetting what century it is and what world surrounds them.

I don’t mean to criticize them too harshly. It's a far more active vision of paganism than I’ve ever been able to achieve, and there are certainly noble intentions involved here. This is the most natural response, too: So what? The entire point of paganism is to bring the old ways back to now. We’ve seen the dire consequences of the modern world, and it is imperative we crush it and return to our roots. This is a huge step in that direction. We know what works, and we’re doing exactly that.

But unfortunately, I sense something is missing from this equation. I do not think it is even remotely possible to just “go back”, nor was this temporally-fixed romanticism the attitude of the very peoples we seek to honor. As it will be shown, there are more problems here than one would assume. We must be more than mere necromancers. I wish to explore why that is, and what about our approach can be modified.

D'où venons-nous? Que sommes-nous? Où allons-nous?

Who are we? Where do we come from? Where are we going?

Why Are We Doing This?

Let us first analyze what the underlying motivations and goals of the pagan resurgence in the West.

It is likely obvious to most that the principle element of neopaganism is a feeling of romanticism, a yearning for the lost ways and traditions of older times. And who wouldn't be inclined towards these feelings? Our society has been torn to shreds by ourselves. We've severed our connection to the land, destroyed our communal relationships, and scrutinized our own existence into nearly nothing. “Tradition” is nearing a slur in our generation. Technology, capital, scientism, and above all else — disenchantment — has left man utterly broken. Western Christianity was this movement's proudest slayed titan.

German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk provides the following to describe the conclusion of this process:

[…]disappointed, cold, and abandoned, they wrap themselves in surrogates of older conceptions of the world, as long as these still hold a trace of the warmth of old human illusions of encompassedness.

Sloterdijk, Bubbles: Spheres Volume I

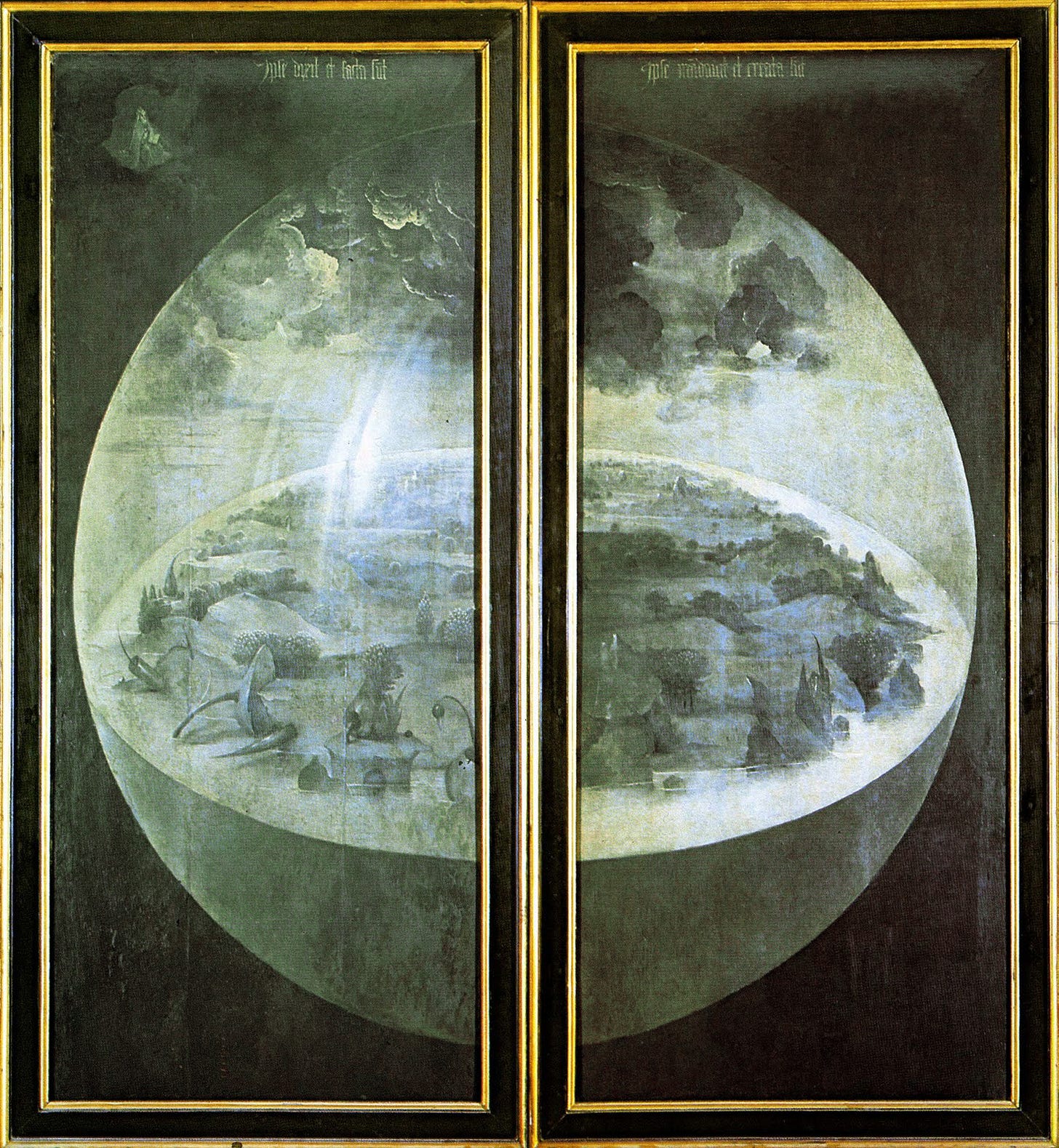

According to Sloterdijk, what happened was a long series of what we would describe in English as “bursting one's bubble”, or in his terminology a “spherological crisis”. As an immunological defense mechanism, man (well-reasoned and in good faith) developed a series of “spheres” to contain itself within and protect itself from the unknown. Society, culture, and tradition served as these membranes. But as time progressed and the world continued to reveal itself, each bubble was popped. Exposed, we seek familiar shelter.

Lets start at the beginning. The world of primitive peoples extended no further than their immediate ecological setting, within which existed an infinite cosmic system. One day a mass of men bearing red shields and golden eagles passes nearby, bearing foreign yet strangely familiar divine figures. Pop. Time passes more, and cloaked travelers bring news of not just a new god from worlds away, but the God, who will see to every need and every victory. Pop. The wheel progresses further… Charles dismantles the warning upon the Pillars of Hercules, adopting the slogan Plus Ultra, and the whole of Earth is uncovered. Pop. The horrors of the 30 Years War pour over Europe, and “God is killed at Magdeburg”—per a truce we still honor, each man is permitted to define his own God, but is on his own to do so. Pop. The Faustian Bargain is struck, and every hidden secret of the natural world is uncovered. Geology, anatomy, evolution. The steam engine, telegram, and camera forces each man to reckon with the sum of humanity. Pop. And finally, the lance of Apollo rockets pierce the atmosphere itself… Pop.

And now in a world with no God, it's just us Prometheans, alone, thinking ourselves to death. As much as we'd like to crawl back into the womb with these romantic efforts, we're learning that it's not so simple. Neopaganism is very much an aspect of that confrontation.

The Problem of Necromancy

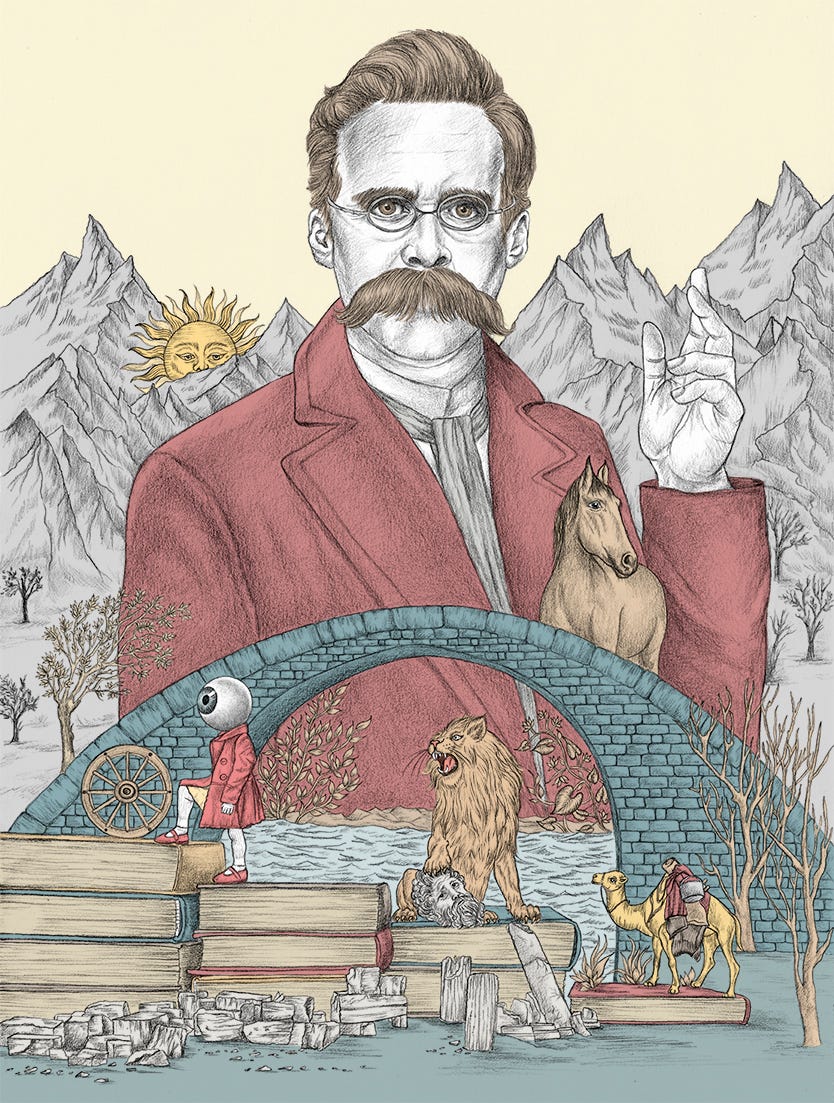

Two thousand years have come and gone—and not a single new god!

Nietzsche, The Antichrist, §19

Everything has changed, and we are naked. Now, like our ancestors pagan and Christian alike, we are forced to explain ourselves. It is not possible to just pick up off where, say, the Anglo-Saxons left off, assuming no reflection or modification is necessary—or worse, sacrilegious! There is just no un-popping the bubble.

Here's one major reason why. In another article, I analyzed a central distinction between the pagan religions of antiquity and the monotheistic sects of Abrahamism as detailed by Robert Bellah. Abrahamic religiosity is centered on revelation, the handing down of sacred texts which contain within them (more or less) a complete religious system. Pagan religiosity is centered on mystical experience, in which the experience of the world itself is the religious system.

This has explanatory power when it comes to not just the differences of pantheons between pagan cultures, but also how they changed over time. These were not due to arbitrary or elective changes of taste, but that they lived in fundamentally different worlds. If the experience changes, then so does the religion. Culturally and ecologically adjacent peoples such as the Germanic and Celtic peoples bear similarities, but as their Aryan cousins marinated in a world as novel as the plains of the Ganges, a divergence occurs. And yet the underlying reality, this “system of experience” for lack of a term, remains the same objective fact at hand across all of reality. This framework can be drawn out over several pages, but I end here for the sake of brevity.

This understanding opens up the problem: our world is, for a number of different reasons, entirely different than the one that existed for the pagan cultures we are attempting to reconstruct. If we cannot experience exactly the same world, then we cannot participate in exactly the same religion.

Much will be different, to whatever significant or insignificant degree that may be. Perhaps the names and attributes of old gods will change, or maybe entirely new ones will present themselves. Certainly, the technological and cultural associations of myth will change.

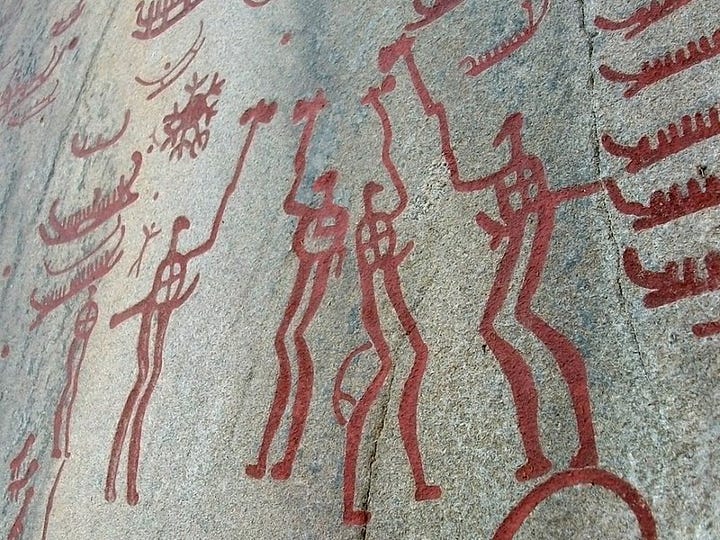

All of this is evident in the literary and archaeological record of pagan peoples themselves. Take for example bronze age the sun wheel, a religious symbol of great significance, yet a technological invention unknown to the first sapiens. Soon later, the sun was pulled by another invention, the horse chariot. Progress slightly further, and we find Nordic longboats transporting between worlds. It wasn't just myth, the gods themselves were named, dressed, and stylized in accordance to the culture of that spatiotemporal setting. One might also include in this argument the arrival of entirely new gods, such as Odin sometime around the turn of the 1st millennia. All of this is to say that simply rebuilding worlds and cultures, arbitrarily selected, serves as an insufficient basis for religion. It’s not what those cultures did in the first place.

This brings us back to that humble temple in Kalliani. Why are they picking this arbitrary point in time of classical Greece, when we know the Greeks themselves had no trouble maintaining a form of controlled religious evolution over its long history? What is it about their approach that allowed them to begin worshiping a “new god” as significant as Dionysus, that we appear to lack?

For us to have a new, living religion, we must undergo some form of cultural and religious genesis. It is insufficient to simply restart what was left 1600 years ago. Otherwise, we are just puppeting a dead body to dance around in a menagerie.

Old Ways, New World

The good news underlying all of this is that these are ultimately technical problems, symptomatic of the curable illness of contemporary sentiments. The core system of paganism indeed remains intact, and the other side of the veil is still accessible. We need only to reach in with an understanding of what exactly it is we're doing, why we’re doing it, and how we're doing it. This is not Deep South Baptism, it is not enough to “just believe!”, serious cultural and intellectual reinvigoration—and indeed, ritual—is required for success.

The solution, I propose, is to not try to revive arbitrarily-selected cultural settings, but to revive the worldview which produced those settings themselves. This worldview has been described by priors in a number of different ways: the common phrasing of “a childlike fascination with the world”, Levy-Bruhl's Monde Mythique, Ronald Hutton's “freshness of perception of the natural world”. Or to cite a contemporary, Bronze Age Pervert's phrasing of “an innocent apprehension of the hidden demons and gods inside nature and things”, and his citing of Houellebecq's strange sadness for a row of coats on hangers.

This process is laid out exactly in Nietzsche's Parable of the Three Metamorphoses in Thus Spoke Zarathustra: First man is a camel, wandering alone in the desert as a burdened pack animal. He then is a lion, reactive, thrashing against the world as he wrestles with the difficulty of creating new values. Finally, he lays down, and becomes a child:

The child is innocence and forgetfulness, a new beginning, a game, a self-propelling wheel, a first motion, a sacred Yes.

Nietzsche, TSZ, I.

More plainly, we must be wildly curious animists. We are currently lions, but a final metamorphosis is at hand.

This is precisely how the paganism we are familiar with originated in the first place. Various forms of animism, shamanism, and mysticism diverging upon tribal lines, and adapting to the blood and soil of its practiced setting. From here, complex myths are developed based on the truth derived from experience, Oracles are established, and strict rituals are performed to maintain the cultural, political, and spiritual ties of its people. There was a very real and serious basis for these things in the eyes of our ancestors, and it wasn’t something as trivial as to “escape modernity”.

We do not know what gods are out there today. Perhaps nothing has changed, not even a vowel of their names. Perhaps everything has changed. But we must have the courage to actually find out, to peer into that dark forest and be open to what reveals itself.

This is what I believe: That I am I. That my soul is a dark forest. That my known self will never be more than a little clearing in the forest. That gods, strange gods, come forth from the forest into the clearing of my known self, and then go back. That I must have the courage to let them come and go.

DH Lawrence, Studies in Classic American Literature

In time, our fascination with the natural world, ourselves as a people, and the relationship between them will develop into an organized religion. And it will not be a hope, it will not be a mere belief in believing. It will be a genuine expression of our spirit, and a living connection with the gods.

Conclusion: A Living Religion

Let us return to Kalliani one final time in conclusion. Were they to read this article, they may reply, “You do not understand. We not only sense but know the gods, just and exactly as our ancestors knew them, and we have benefited greatly from rekindling our relationship to them. The world may be different, but we are no different than our ancestors.” And in many ways, they may be correct. Maybe I am too skeptical and blind to a genuine revival of their religion.

But the criticism that such a revival must in some sense adapt to the modern world maintains its force. We can’t dress up in the skinsuit of ancient Greece forever.

There is actually a good example of an ethnic religion which has undergone such an evolution while retaining its roots, and it surprisingly comes from Christendom. I am speaking of the Russian Orthodox church. Despite being an institution with regional ties dating back to the 800s, it is effectively a religion that is culturally, politically, morally, spiritually, and ecologically by and for the modern Russian state and people. They did not simply dress as Byzantines and mold a copy of the Hagia Sophia, they innovated and projected a genuine spiritual expression of Russia.

And this extends to the aesthetics of modern Russian religion, too. See the much-appraised Main Cathedral of the Russian Armed Forces in Moscow, completed just 5 years ago. On the exterior it presents itself as a familiar golden-domed basilica, but on the interior is housed both old and new. The typical gold halo mosaics of saints line the walls, but the style and lighting bears a neo-futuristic spirit. Below the heroes of the ancestral Rus are artillery batteries and Red Army formations. Russians may come here to visit shrines immortalizing family who were killed in battle just 80 years ago. It is a genuine work of art, and a beautiful expression. More importantly, it is a courageous toying with the boundaries of “safe” cultural practices, while remaining true to the entire point of it all. A rarity in the West.

As a result, there is a certain vitality that is evident here. Unlike the rotting den of humanitarian NGOs that has become of St. Peter’s in Rome, this church is alive.

I believe something similar, perhaps even greater, is very much possible for paganism as it seeks to reappear. I do not expect tiny Greek villages to compete with Moscow. However, it does show that even the most dogmatic religions can handle evolution. More importantly, it can handle the modern world. That is exceptional news for a religion which seeks to confront it directly.

But we have a long way to go, and much is to be done. I do not claim to know exactly what the exact output of our new paganism should look like. For now, I can only advocate for calling into that clearing of the dark forest, and waiting for a reply—be it from strange or familiar voices—rather than simply anticipating an echo.

These are exciting times. The legacy of pagan Europe has inspired great eras of cultural ascension before, and I look forward to it doing so again.

Cited Works

Bubbles, Vol. 1: Spheres, Peter Sloterdijk

Old and New Paganism, Bronze Age Pervert

Suggested Reading

Summoning the Gods, Collin Cleary. An exhaustive work on paganism which takes a similar approach, but in greater detail.

On Being a Pagan, Alain de Benoist. A foundational work on right-wing paganism, dealing particularly with its anti-Christian element. However, Benoist writes at length about a new “Faustian” paganism versus the old.

The Mythical World, Levy-Bruhl. Through the aboriginals, this cornerstone anthropological work gives great insights into what primitive religion was like.

Thus Spoke Zarathustra and The Antichrist, Nietzsche. For a full-context reading of his aphorisms cited here.

Man, I really thought I was the only person writing about spheres in that way. His interpretation is much more rounded (kek) and well-thought out than mine, but I've taken this concept of spheres and domains more in a religious than a social sense.

This is a great article, and one that I have been wanting to write but it is hard to find the words for this. It's hard because I have already experienced a level of hierophany that made me convert to folkism. Secondly, I know many people with bona fide faith in the Norse Gods and even have moving accounts which compel me to believe certain things. For example, a story about an infertile woman married to a devout pagan, she was given a fertility ritual and I believe passed through a stone (unsure) and later she had a dream where two ravens told her she would have a girl and to give her a specific name. This woman probably heard about Odin's ravens some time beforehand, but she really had no idea what anything meant and just mentioned the dream offhand to her husband because she was more interested in the name and didn't get the possible significance. Now, things like this are proof only to those who already have experienced something of this regard. How often does this truly happen in the pagan revival? How often do people have bona fide hierophany? I don't know if it can be quantified.

Kind of what I am getting at is this: there are already men and women who feel or perceive the Old Gods as being active in our lives. The Weave of Wyrd, no matter what men call it, still exists and is still being woven. I do often wonder if there has already been a Ragnarok, and the Norse Gods are dead, and if the Gaelic Gods are truly just secured away on an island beneath the western sea waiting for some divine erdathe. I just don't know.

But I am compelled to believe that the Gods *are* still active, and that new powers *are* being identified. The tapestry is tattered and torn, yet we are still adding to the threads with each successive generation. Who is Columbia if not the manifestation of the American folkish spirit? She should be supplicated to by folkish Americans. Who is Adolf Hitler if not another Germanic hero akin to Arminius? He should be revered by folkish Germans.

This is a damn fine article, and I like how you navigate this controversy. In my eyes, the story is not over. It never ended. Instead of thinking about the death of the old world and its resurrection (reconstructionism) - we should instead focus on our lived experiences and ancestry (continuism). My 2 cents, at least.

“they don’t believe in their gods, they merely believe in believing them” is a good summary of the problem. Without the supernatural, it’s all just kind of a LARP. Once established, religions can run on fumes for quite a while - you get a lot of “cultural Catholics” and “cultural Jews” etc that way - but without the miracles, eventually they run out of gas, as has happened across much of Christendom.

fwiw, the same is true even of Russian Orthodoxy, which I agree does have more vitality than many western churches. Russians do consider it part of the Russian identity and as Russia itself has risen from the nadir, so too the Church has felt more alive… but monthly church attendance is somewhere in the mid-single digit percentage of population. It too smacks of “believing in belief”.