Book Review: The Germanization of Early Medieval Christianity

An Overview of an Important but Overlooked Book

On a religiocultural level, this schism [between Vatican II and the SSPX] may be considered the end of the image of the Roman Catholic Church as a popular expression of European Christianity. For at least the preceding millennium, from the coronation of the Saxon King Otto I as Holy Roman Emperor by Pope John XII on February 2, 962, to the opening of the Second Vatican Council by Pope John XXIII on October 11, 1962, the religiocultural orientation of popular Roman Catholicism was predominantly European and largely Germanic. An example of a popular pre-Vatican II Eurocentric view of Christianity has been provided by Avery Dulles in his study The Catholicity of the Church, where he cites Hilaire Belloc's affirmation, “The Faith is Europe. And Europe is the Faith.”

James C. Russell

n a sphere that frequently debates the character of the West, race, Christendom, nations, and their resultant greatness, very rarely is a proper account of the nature and genesis of these things provided. As is unfortunately often the case, these discussions rapidly disintegrate into heuristics, conjectures, and myths with little actual history involved. Did you know that the Crusaders were actually pagan? Did you know that Jesus personally charged Martel to save Europa? Did you know that Europe was a backwater of savages until the cross glistened over its fields? Did you know that the pagans never actually converted? Did you know that […] enough, you’re Jewish!

Recently, a book has gained some popularity within the online right that provides a clear anchor of a serious, scholarly work that deals with this general topic directly. I have read it a few times, and enjoy it more and more with each trial. This is James C. Russell's The Germanization of Early Medieval Christianity: A Sociohistorical Approach to Religious Transformation. This book is Russell's revision of his doctoral thesis in historical theology at Fordham University and is therefore very academic in nature.

A little background on Russell: I think it is fairly obvious he is familiar with the content and worldview of the right. He cites hereditarian genetic studies estimating the heritability of religiosity, stating that religiosity has a clear biological and ethnic component. He also authored a now-extinct book on Christian NGOs titled Breach of Faith: American Churches and the Immigration Crisis, where he cites work such as Sam Huntington's Clash of Civilizations. He has also spoken at events hosted by the Asatru Folk Assembly in the past. I don’t want people to think Russell is aiming for a typically anti-Christian, secularist academic work. Rather, he seems to have beliefs that align with our own and treats historical Christianity with incredible generosity and fairness.

In my opinion, this is a fantastic book that I cannot say enough good about. I consider it one of those “worldview shaper” books that fundamentally alters the reader's understanding and rationalization of history and religiosity as it pertains to the Western story. I give it this label for two reasons: Firstly, it is an absolute treasure trove of historical sources and works by renowned historians on the topic and era, especially for lay readers such as myself. You may not know who Carl Erdmann, Ronald Hutton, or J.M. Wallace-Hadrill are or what they wrote about before this book, but you will after. You may be unfamiliar with the writings of various crusaders like St. Bernard of Clairvaux or the Gregorian missionaries such as Mellitus, but no longer. Secondly, it rather conclusively settles the issue of “race versus religion” once and for all at a ceasefire line that both sides ought to be happy with. Rather than one triumphing over the other, each feeds into the other, changing the other as much as itself. A proper historical understanding of both the Germanics and Latin Christianity, and how they merged to create “Europe”, can be obtained by an honest and interested reader.

Since this book is often cited but rarely read, I would like to take the opportunity to give a general summary (and in some parts, a defense) of Russell's work, and then provide some commentary on the applications more specific to the arguments frequently had in our sphere. Above all else, it is my hope people read and understand this work, but they can refer to the summary presented here as a quick overview per my own reading and understanding of it.

As unfair and risky as it is to condense the book into a few paragraphs, I will do my best so that those who haven't read it may have a general sense of what I'm talking about when I move into a larger discussion about its points and findings. The book deals with two central concepts: Christianization and inculturation. Those being, what does it mean for a people to become Christian, and what meets that definition? When a people is converted (in our case, the Germanics), what influences do they exert on the religiocultural attitudes of the religion itself? I don’t expect Russell’s arguments on what constitutes a Christian or Christianity to find much controversy, but the concept of inculturation certainly will.

The unavoidable reality that the book does a good job of stressing is that conversion is not always a one-way street. Depending on the sociohistorical context of the conversion and the methods used by missionaries, the people can reinterpret the religion to their ends as they are being converted. Indeed, the sociohistorical context of the Germanics of the early medieval and the method of accommodation practiced by leaders such as Pope Gregory the Great were ripe for the Germanic inculturation of Christianity. Russell explains:

This observation is not intended to detract from the overall effectiveness of the Church's missionary policy. In fact, it is quite possible that if doctrinal assent and ethical modification had constituted a prerequisite for baptism, those Celtic and Germanic leaders whose own baptism often precipitated that of many of their kinfolk might well have rejected Christianity outright owing to its obvious ideological opposition to their Indo-European warrior code. Thus the Christianization policies of accommodation and gradualism were effective in incorporating the Germanic peoples into the Roman Catholic Church, but at the same time they led to a substantial Germanization of Western Christianity. The early medieval Germanization of Christianity, in most cases, then, was not the result of organized Germanic resistance to Christianity, or of an attempt by the Germanic peoples to transform Christianity into an acceptable form. Rather, it was primarily a consequence of the deliberate inculturation of Germanic religiocultural attitudes within Christianity by Christian missionaries. This process of accommodation resulted in the essential transformation of Christianity from a universal salvation religion to a Germanic, and eventually European, folk religion. (pp. 38-39)

Pagans often make polemics that “they didnt really convert”, or “they were lied to”. Certainly, there is an element of truth to this: in an attempt to accommodate Germanics, missions presented a version of Christianity that was radically different in character than what was familiar to the Greeks and Jews of the 1st and 2nd Century Early Church. Rather than emphasizing salvation and apocalypse, which had before appealed to the urban centers of the crumbling Roman Empire, the Germanics were sold a Christianity that emphasizes the power of God and his saints/angels to provide temporal needs (such as victory in battle, as provided to Clovis at Tolbiac), and a martial, world-accepting, and folk-centered religiocultural worldview.

However, it is important to emphasize that neither side was being dishonest. The Germanics came to earnestly believe in the power of Christ the Savior and utterly depend on the legitimacy of the Roman Church on a level that is hard for the modern mind to fathom; nor was the Church intending to keep their converts in the dark forever or abuse them to its own ends. The method of conversion for the medieval Church is somewhat foreign to us, especially in Protestant America. Baptism, rather than a final ritual of the persuaded, is Step 1. Then education of church teaching begins, and this takes several generations. It is merely that, for a number of reasons which the book details, the reverse pressure of Germanicism on the Church did not make the Germanics into Christians of the flavor of the 1st Century witnesses of the Resurrection. Rather, it produced a fundamentally Germanic reinterpretation of Christianity, which we now know simply as Christendom. It is the water of the ocean that we fish of the West obliviously swim in every day. When people speak of Christianity, it is often this specific cultural interpretation of the Gospels that is being referred to, rather than the Gospels themselves.

Russell illustrates this transformation perfectly through the long-haired progenitors of the Franks, the Merovingians. They were fiercely war-like and brutal, they relied on deeply held attitudes towards kinship and inheritance (it is from they we have Salic Law), and rooted their religiosity in the concept of sacral kingship. That is to say, the Merovingians were pagan to their core. And yet, they were resolute defenders of Christendom, piously devoted to the Trinitarian, crucified God, and the very founders of Western Christendom itself. How did this happen, and how does one explain the discrepancy?

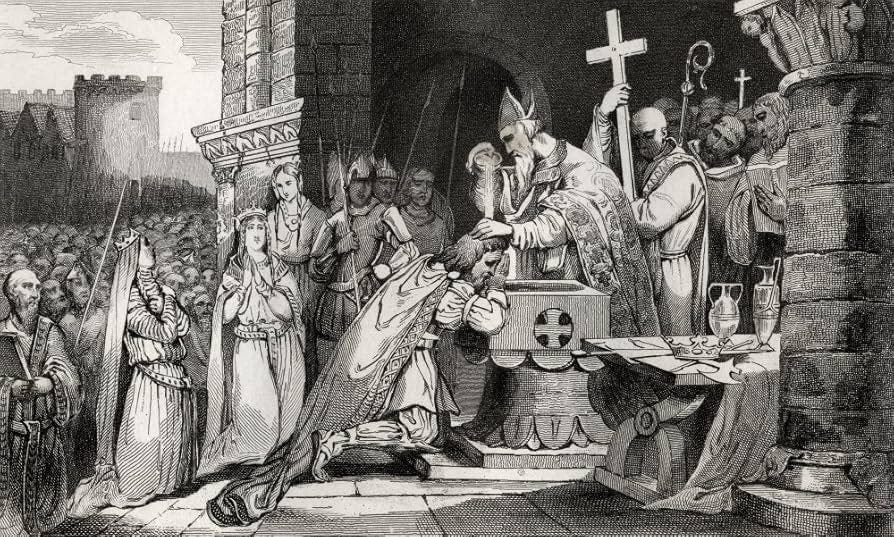

Following the fall of Rome, Gaul was ruled by pockets of Gallo-Roman aristocrats and Christian clergy who now had to contend with the swarms of Germanic barbarians filling the void during the Great Migration. This Gallo-Roman aristocracy was, in effect, the Christian Church's inheritance and continuation of the Roman imperial state itself. This provided an opportunity for both parties that was reminiscent of old Romano-Germanic agreements: the Church desperately needed fighting men to protect it, and the barbarians deeply desired the splendor and legitimacy of Rome. It was a match made in Heaven: roughly two centuries later, the Frankish warrior-king Charlemagne would be crowned as Karolus Augustus, Imperator Romanum, of the Holy Roman Empire, in Rome, on Christmas Day, after a mass in St. Peter’s Basilica. This friendship and eventual synthesis is more than metaphor or coincidence, it is the literal story of how pagan Europe made Christianity into a Christianity of its own.

One clear example of a position of the Church’s that changed towards the Germanic perspective (and Russell gives us plenty… liturgy, ritual, feasts, votive masses, to name a few…) is the Christian attitude towards war. The position of the Germanics and the Early Church couldn’t be more different: for the latter it was to be avoided at all costs, predominantly leaning on the pacifism and nonresistance espoused by the Sermon on the Mount (to the great benefit of underground churches avoiding Roman persecution). But for the Germanics, war itself was a religious undertaking, and was actively sought out for its own end. How, then, was one of the most militaristic peoples in the world integrated into a religion which preaches pacificism and nonviolence? As mentioned before, the synthesis comes from the Church’s need for warriors, and the Germanics’ need for renown. The end result is the invention of something that Europe nor Christendom had yet seen: a Holy War. The Normans on crusade, Martel defending the shrine of St. Martin at Tours, the formation of military orders who fight to the death in service of their Lord… all of this has a clear and substantial Germanic element that could not have been anywhere else on Earth. Russell quotes the renowned historian Carl Erdmann on this topic:

Nevertheless, the German mentality also exercised a positive influence upon the development of the ecclesiastical morality of war. When the church encountered pagan elements that it could not suppress, it tended to give them a Christian dimension, thereby assimilating them. This happened to the ethics of heroism. The whole crusading movement may justifiably be seen from this perspective; Christian knighthood cannot otherwise be understood. This evolution began in earnest only around the year 1000, but prefigurations of it do, of course, appear earlier. To some extent, the development of the Christian cult of the archangel Michael symbolizes the process.

Origin of the Idea of Crusade, pp 19-20

On this topic again, Russell gives an interesting anecdote about regional variations within Western Christendom, emphasizing just how important the “Teutonic” element is to this point:

The impact of the Germanic warrior ethos on the Lives of early medieval hermits was not, however, relegated to the realm of metaphor. In a regional comparison of hermits' Lives, Howe concludes: "Hermits who are literal soldiers are a northern theme. Northern 'servant of God' phrases too show a 'vir Dei' who is more often an 'athleta,' a 'miles,' a member of the heavenly 'militia' than are his Mediterranean counterparts. Overall these combatants are in somewhat different fields—the Mediterranean hermits fight more interior battles against their flesh, against demons who attack their perceptions, and they are 'slaves of God' in undertaking these combats; while the northern hermits, on the other hand, fight more concrete external opponents, are more literal soldiers, and are hailed as 'men of God.'“ (p. 125)

The book begins with the objective to investigate to what extent the Germanics of the medieval were “Christianized”, and what that entails. Russel ultimately concludes that the Germanics had not by the end of the early medieval. However, in the midst of that investigation, Russell uncovers that this question is far more complicated than originally thought, as the Germanics had completely redefined what Christianity was. Surely, they were just as concerned with the death, resurrection, and eternity of Jesus Christ as the several centuries of Christians preceding them. But if one defines a Christian based on the beliefs, attitudes, values, and behaviors they espouse as a result of their religious worldview, then the picture is quickly complicated by the fact that the Germanics had reinterpreted the beliefs, attitudes, values, and behaviors of Christendom itself. More importantly, as the heirs of Rome and eventually the only Christian powers left on the planet, the since-Germanicized Western nations defined what Christianity was for much of the rest of the world, particularly in the context of the later pre-modern era of colonialism and Reformation.

Though this may come off as a polemic against Christianity, again, I urge you to reconsider. When Christians in our times lament the feminization, globalization, and liberalizing of their churches, to which eras and individuals do they turn to for inspiration? Charlemagne, Alfred, and Otto. They get teary-eyed watching the cross and holy banners glisten in Kingdom of Heaven, they emulate the chivalry of the crusading ethic, and above all else they dream of returning to “High Christendom”, an era of distinct nations unified under the cross filled with culture and heroism. They are dreaming of not the Early Church of Peter and Paul, but of precisely the Germanic reinterpretation of Christianity that Russell has laid out. More generally, they are dreaming of a Christianity that permits them to make such cultural reinterpretations at all.

This problem of resolving fundamental metaphysical differences between ethnicities who ostensibly share the same religion is a personal a project of mine, although within a pagan context. The solution could be in phenomenology, and an understanding that religiosity is an objective reality as it appears subjectively to a specific people. Christians may find utility in applying this framework to their own religion.

Pagan Phenomenology I: What is a god?

This is part 1 of a 3-part series on my view of a pagan religious system heavily influenced by the works of Collin Cleary, Husserl, Heidegger, and others. Part 1 will describe phenomenology and how it can apply to paganism. Part 2 will set up a hierarchy of being and transition into Heidegger's contributions to ontology. Part 3 will suggest practical ad…

When I was old enough to give serious thought to religion, I had already largely abandoned Christianity for reasons I could not yet properly articulate. In adulthood I had decided to give more traditional conceptions of Christianity (Catholicism, etc.) a chance, and embarked on a long intellectual journey to see if it could work. Something was indeed drawing me to this traditional version of Christianity. I began reading Aquinas, medieval history, C.S. Lewis, the whole lot. This book, however, was the end of that journey.

What I had uncovered was that the elements of Christendom that appealed most significantly to me—its history, its heroism, and its fundamental relationship to Western culture—were not exclusive to Christianity, but to a significant degree a work of the Germanic spirit. Conversely, the elements that appealed least to me—its soteriology and concept of sin, its Great Chain of Being, and its life-rejecting worldview—were indeed exclusive to Christianity, and were saturated within the Early Church. There is, after all, a reason why we love the medieval so much while Engels (and leftists today) adored the Early Church. I was then, and still today, unable to reconcile the discrepancy between the medieval and the Early Church. More importantly, I was presented with the source of my fixations. Effectively, this book had in my mind closed the door to Christendom and opened another to paganism.

I understand not all will not have the same experience and I do not expect that to be the takeaway. The primary takeaway I wish readers of this article, and hopefully the book, is that religion exists in cultural, historical, and indeed ecological & biological contexts. While conversion certainly demands changes to one’s beliefs, when done at scale the converted will often reinterpret the presented image into a familiar context. Germanization was not the only time this occurred. Before Christ was even born, the Levant had already experienced a dramatic influence of Hellenic culture and religious concepts. The immortality of the soul, the apocalyptic style of the Book of Daniel, the cosmological argument, and the nature and content of the Messianic prophecy itself were all saturated with Hellenic contributions, and ultimately written in Greek. As it moved into Rome and later Gaul, Christianity adopted the role of a religion charged to the duty of an imperial state. Could the temporal power of the medieval Papacy be explained without the influence of Roman civics? I don’t think anyone could argue otherwise. Religion evolves with its people, even ones that claim to be above “mere flesh”.

I will leave off with a thought experiment and consideration for the future in conclusion. Given this analysis of how the dominant culture can shape the very content of a religion and interpretation thereof, what do people expect will happen as Christianity continues to globalize? As Christianity wanes in relevance in Europe, and explodes in Africa and Latin America? What will African Christianity look like, and how much will Westerners such as ourselves be able to understand it?

For obvious reasons, I think it is best we leave this project to the Africans, and worry about our own religiocultural problems. Russell’s book provides an exceptionally well-done work to understanding these problems and how to go about resolving them. Give it a read!

(Updated) Oh, yeah! Blood select culture, culture select blood. Much as a man and a woman would shape each other.

After some thought, I disagreed about the idea of Holy War being new with Christendom. All wars is holy war for the Pagans as they are the ancestral cult. With their numbers so small, their health and tomb are always endangered. Failure to overcome danger or to have children run the risk of leaving their ancestors spiritually hungry and without a chance for reincarnation within their bloodlines. This is why there are the gods and goddesses of war, even Zeus and Jupiter are warriors.

As for the Hellenic inculturation, the best book about this is Plato and the Hebrew Bible with a very through review here: https://vridar.org/series-index/russell-gmirkin-plato-and-the-hebrew-bible/

What do you think of the belief that the Catholic Church was deliberately shaped by Constantine et al into something resemblant of the Roman state religion? Is Germanic influence stronger than Latin influence?